Advanced authoring in Microsoft Word – Part 1: Introduction to styles

The most basic principle related to digital word processing is the separation of content and presentation; you should not mix these.

For example, suppose you want to create a heading. You could enter the heading text (the content), select it, and then apply some presentational attributes directly to it (large text size, boldface, maybe coloured, maybe underlined). Then you have mixed content and presentation. Notice that you need to memorise the font settings and repeat the exact same font commands every time you write a new heading of the same level.

Or you could enter the heading text and tell Word that the current paragraph is a heading (and what level it has); in other words, you tell Word what logical type of paragraph it is. In this case, you only specify the contents, and leave the styling (or presentation) as a separate question to be dealt with later. Knowing that the paragraph is a heading (of some level), Word will automatically style it using its default presentational rules for such headings (large text size, boldface, …). These presentational rules are associated to the heading (of that level) as a type of paragraph, and not to the particular heading you just entered. Consequently, you have separated content and presentation. Of course, you may change the presentational rules associated to each logical type of paragraph (like the different levels of headings), so you still get perfect control over the appearance of the document.

As a concrete example, consider the following very primitive document. The document consists of two sections, each with its own heading. The first section contains three paragraphs of text, and the second section contains one paragraph of text.

| Direct formatting | Separation of content and presentation |

|---|---|

Content:

| Content:

The document also contains a ‘style sheet’ that specifies the presentational attributes of each logical type of paragraph:

|

In the terminology of Microsoft Word, the ‘types’ of paragraphs are (somewhat unfortunately) called ‘styles’. Hence, the good way of using Word is to use styles, to separate content from presentation. Technically, in Word, a ‘style’ is not much more than a named set of presentational attributes and each paragraph in the text is associated with some particular style. In the very simple example above, two styles are used: ‘Heading’ and ‘Normal paragraph’.

There are only advantages to this approach:

As already hinted, it becomes much easier and much more convenient to write the text since you do not have to keep entering the same presentational attributes over and over again. You only need to specify the type of each paragraph (like ‘Heading 1’, ‘Heading 2’, …, ‘Warning box’ etc.).

All body text, headings of the same level, figure captions, warning boxes, block quotations, and other logical kinds of paragraphs will necessarily be given the exact same formatting throughout the document, which makes the document look professional.

There is also a huge benefit in terms of maintainability.

Suppose you have a 750-page document with a lot of headings and you realise that you want to change the colour of every instance of the third level of heading throughout the document. If you have not separated content from presentation, you have to find all instances of third-level headings, and change these one at a time. (Of course, there is a risk that you’ll miss one or two of these instances, making the document look bad.) On the other hand, if you have used styles, you simply have to change the formatting of the ‘Heading 3’ style, and the entire document will be restyled automatically.

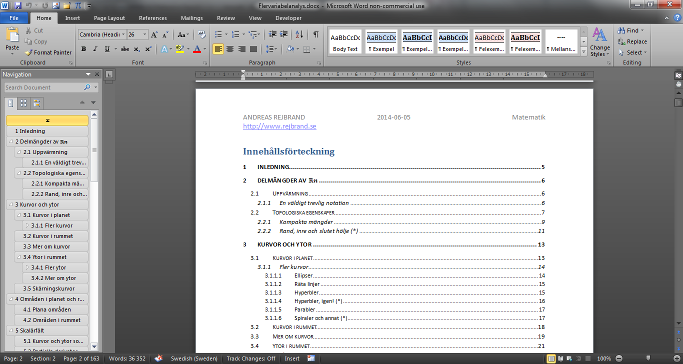

Since Word knows the outline of the document (that is, the heading structure), it can automatically create a table of contents (TOC). This can be shown in the user interface and it can be included in the document itself. In either case, it is automatically updated when the document is changed. Creating a TOC manually in even a moderately large document, and keeping it up-to-date as you work on the text, is almost unfeasible.

In the screenshot above, both examples of TOCs are shown. (Another thing that is shown is an annoying limitation of Microsoft Word: while the second top-level heading contains the mathematical symbol ℝn, the superscript is simply ignored in both TOCs.)

If the document is marked up appropriately using styles (that is, headings, warning boxes, and other special types of paragraphs are given appropriately-named styles describing their type), it is easy to restyle the document, as suggested above. You only need to change the presentational attributes of the styles; you do not even need to touch the content. The same content can thus easily be used to create documents with very different visual appearance. (In Word, restyling is essentially restricted to fonts and things like paragraph spacing, border, and background colour. In HTML, on the other hand, two different style sheets can produce vastly different results from the same hypertext content.)

Search engines and assistive technology software (such as screen readers for the visually impaired) will understand the structure of the document better if it is marked up semantically. For example, the user can ask the computer to enumerate the headings, or to go to a specific heading. Or the user could ask the computer if there are any warning boxes in the text. (However, semantic mark-up is more refined in HTML compared to Word.)

The reason why the ‘types’ of text are called ‘styles’ in Word is rather obvious; indeed, a ‘style’ contains information about the visual presentation, or style, of the paragraph and its text. However, a better term would be ‘type of paragraph’, or ‘class’. Indeed, the names of the ‘styles’ in the first example are ‘Heading’ and ‘Normal paragraph’, which describe the logical type of paragraph. In particular, the names are not ‘Big blue and bold text’ and ‘Small text’ which would describe the presentation. In addition, it is perfectly reasonable that the actual presentational attributes will change in the future (maybe the headings will be red instead). If so, the name ‘Heading’ will still be valid, but ‘Big blue and bold text’ might not be valid any more.

Also, in theory, the types of paragraphs are not only about presentational attributes (like font settings and paragraph spacing). Instead, the type also has semantic meaning by itself. For example, headings create the structure of the document (which can be used to navigate the document and create automatic tables of contents). For instance, it is certainly possible that there are two ‘styles’ (‘classes’) that have the exact same presentational attributes, but differ in semantic meaning. One plausible example is ‘Heading 5’ and ‘Keyword’, where the first is the fifth-level heading and the second is used to highlight keywords in the text. (Perhaps both are blue, bold, and 11 pt.) Although their ‘styles’, in the sense of presentational attributes, are identical, only instances of the first one will participate in the document outline and be displayed in TOCs.

As a second example, if you write a mathematics textbook, you can use a special ‘style’ (or ‘class’) named ‘Definition Box’. Not only might this be used to create a black solid border around the paragraph – you can also tell Word to extract all the definitions in the text and create a list of them (at least in theory).

Consequently, the point is that a ‘class’ (or ‘style’ as it is called in Word) has semantic value on its own. The fact that you can connect presentational attributes to classes is only one of the applications of classes.

From a more abstract point of view, the fact that the ‘classes’ should be named after the logical types of the paragraphs and not after the presentational attributes associated to them also follows from the general rule that content and presentation should be separated. Since the classes are associated to the content, they must not make references to any particular presentational attributes.

In conclusion, so far:

Never apply presentational attributes (such as font or paragraph settings) directly to the text.

Instead, make sure that every paragraph has the right style, like ‘Normal’, ‘Heading 1’, ‘Heading 2’, …, ‘Figure Caption’, ‘Example Heading’, ‘Definition Box’, ‘Theorem’, or ‘Proof Box’ which describes the semantics (or type) of the paragraph.

Then adjust freely the presentational attributes of the styles.